Memoirs of public figures, written by family members or (former) friends, are often as revealing about the person who wrote the memoir as about the purported subject. Or, to put it differently, such memoirs are really about the relationship between the subject and the writer. Paul Theroux’s Sir Vidia’s Shadow: A Friendship Across Five Continents (1998), for instance, presented a scathing portrayal of V.S. Naipaul, which focused on his personal failings rather than his literary achievements. While informed by a complicated past friendship, Sir Vidia’s Shadow nonetheless gives us valuable insights into Naipaul’s contrary personality and, ultimately, the manner in which this is reflected in his literary work.

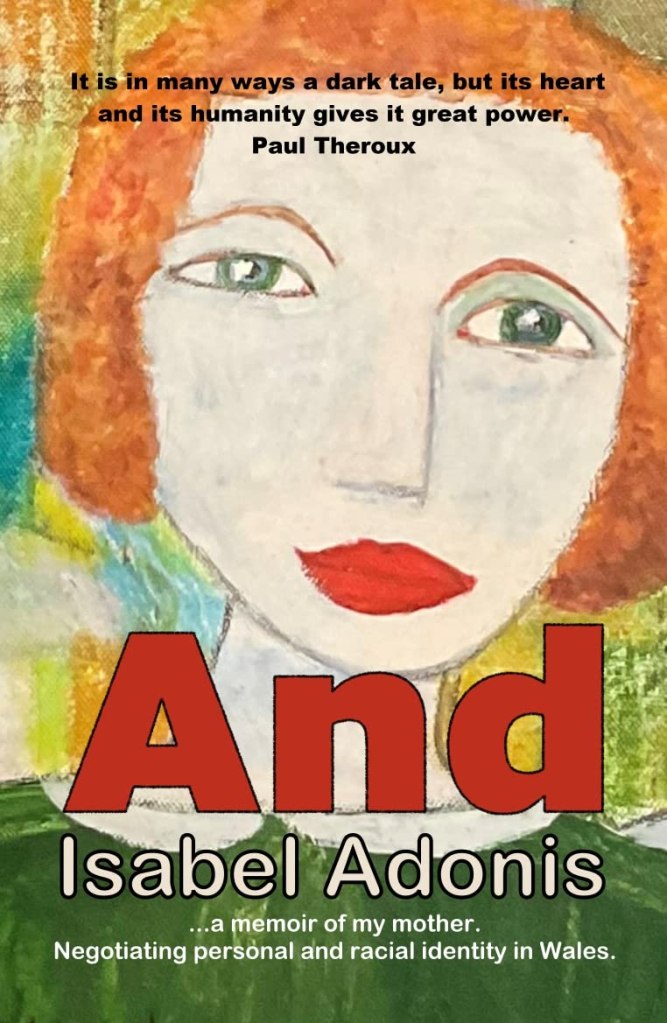

This came to mind when I came across And: A Memoir of My Mother (2022) by Isabel Adonis, who was in fact encouraged by Theroux to write this book. Isabel Adonis is the daughter of the Guyanese artist, archaeologist, writer and cultural administrator Denis Williams and Catherine Hughes, a Welsh woman who was his first wife. Adonis is herself also an artist and a writer, now based in Wales. And: A Memoir of My Mother is her first book. While she chose to dedicate her memoir to her mother, rather than to her famous father, the persona of Denis Williams looms large over the book. And it is of course because of its association with Denis Williams and Caribbean cultural history that the book came to my desk for review. I could not help but reading it in those terms.

Isabel Adonis’ memoir is not set in Guyana, where she has never lived, but in Wales, England, and Sudan, and focuses on the years her parents were together and the aftermath of their marriage. Denis Williams abrupt abandonment of his first family when he returned to Guyana in 1967, with another female partner and their child in tow, is the pivotal, defining moment in the memoir. In addition to the personal trauma, Williams’ departure left the family in acute debt, leading to the loss of the family house in Wales. Adonis had only very limited and fraught contacts with her father subsequently.

Denis Williams is described as a distant, self-absorbed and emotionally inept father, who was far more preoccupied with his academic and artistic work, and his postcolonial identity quests, than with the welfare of his family, while her mother was the one keeping everything and everybody together, while also providing uncredited creative and intellectual support to her husband’s early career. The portrayal of her mother implies that she had an original, rebellious mind, and a creative intellect of her own. As Adonis puts it: “her making things and making do were her art” (p.50) but later on, talking about her mother’s death, she wryly adds: “my mother wasn’t in the Guardian” (p. 155), while her father was publicly eulogized, in Guyana and the UK, when he passed.

Such family dynamics, with the expectation that the “wives” were to be impeccably self-effacing with their support for the “big men” in their lives, were of course not unusual at that time. There is a clear pattern to that effect in the life stories of mid-twentieth century Caribbean “big men,” the pioneers of postcolonial thought, politicians, and cultural figures alike, several of whom had also married white European women, with relationships that were loaded with complicated racial, cultural and social class tensions. The story of Naipaul and his first wife Patricia Hale, who was English, certainly comes to mind and the entitled callousness with which he treated her was a much-noted consideration in Theroux’ earlier-mentioned memoir. Theroux had, in fact, met Denis Williams and Catherine Hughes in Uganda in 1966 and in later correspondence with Adonis noted the similarities between the two men. Adonis’ decision to dedicate her memoir to her mother represents a pointed challenge to those patriarchal dynamics.

Catherine Hughes was, if anything, an unconventional woman who challenged the restrictive social codes of her time and place of origin. As an orphan who had been abandoned by her philandering father after the early death of her mother, she had her own history with paternal neglect. She had her first child, her daughter Janice with an African American serviceman while still in another marriage, and then married Denis Williams in 1951, when he was a young art student on a British Council scholarship in London. They had four children together, all daughters, with Isabel Adonis as their second child. The family first lived in London and then in Khartoum, where Denis Williams taught fine art at the Khartoum Technical Institute for several years. Her mother decided to move back to Wales in 1959, when she was pregnant with her fourth child, and after that maintained a visiting relationship with Williams while he continued working in Sudan and, subsequently, in Nigeria, at the University of Ife, and briefly also in Uganda, at Makerere University.

During the early years of the marriage, the family had experienced material hardship and lived in a cramped two-room flat on Oxford Road in post-war London. Adonis’ recollections of that moment offer a vivid portrait of that challenging but rapidly changing social environment. That moment is, not coincidentally, also portrayed in Denis Williams’ early painting Human World (1950), which speaks to the momentous social changes the UK was going through as it became a multicultural and multiracial society during the postwar reconstruction. The contrast between the two portrayals is instructive: while Adonis’ account is intimate and unembellished, narrated as lived and observed by a young girl, with moments of pain and wonder, Denis Williams sought to represent that moment in iconic, generalized and monumental terms, from the self-conscious perspective of a mid-twentieth century Caribbean artist and intellectual.

The move to Khartoum represented a vast improvement in the material conditions and social status of the family. But there too, they encountered the contradictions of racism and classism when the teacher in the Anglican school for expatriates in Khartoum, on seeing the biracial Williams girls, blurted out that “we don’t have those kind of children here.” (p. 70) The expatriate community in Khartoum was however also a place in which the social power of her mother’s whiteness was readily asserted, and the teacher was summarily dismissed and sent back to England after she made a complaint.

And: A Memoir of My Mother is not informed by archival research, interviews, and personal papers, as more formal, official memoirs usually are, but by personal recollections and stories informally relayed by others. It is not concerned with “hard” historical facts, but with the subjectivity of lived and remembered experience, and rooted in the ties of family and community. In fact, it represents an implied and rather subversive rejection of “big history” or rather, the histories of “big men.” Throughout the book there are hilariously off-handed remarks about the “big names” in her father’s life, such as: “as he spoke he mentioned many famous people and some of them he mentioned as if they were his friends” (p. 94) or, talking about her parents’ social life as part of the expatriate elite in Khartoum: “and sometimes my mother and my father went to parties at the palace, and my mother once told me that she had met Haile Salassie [sic], but I didn’t know where and I didn’t care.” (p. 68)

In one segment of the book, Adonis is openly critical of Denis Williams’ inability to move beyond his intellectualism, which she describes rather scathingly as a lack and a failure: “His book, Icon and Image is written in the language of scholarship and he is a scholar for scholars and this book was not written for the African and it was not written for the people who produced the sacred art, the metal workers and the people who worked in the bush and who walked miles in the bush with a small piece of cola nut. It was not for them. He describes the rules of metal casting but not what is sacred and not what is special about the Yoruba people and it was a triumph of intellect over emotion.” (p. 115) Such disconnect has of course been part of the predicament of the postcolonial intellectual, and I could not help but being reminded of Frantz Fanon’s caution, in The Wretched of the Earth (1961), that “the culture that the intellectual leans toward is often no more than a stock of particularisms. He wishes to attach himself to the people; but instead, he only catches hold of their outer garments. And these outer garments are merely the reflection of a hidden life, teeming and perpetually in motion.”

Adonis’ approach to her memoir stands in striking and quite deliberate contrast to Denis Williams’ compulsive intellectualism. The book is not written in academic language, but has a strong oral, at times even child-like quality, and becomes a praise song in certain parts and an elegy in others, with repetitions of entire passages that sound like incantations. And this informal, meandering, and indeed performative tone is part of what makes the book a compelling and engaging read, which I finished in one go, although I had to go back to it several times to capture some of its nuances more effectively.

Her mother’s life story is sketched in richly textured and empathetic detail, while her father remains emotionally opaque, with only the occasional glimpse of his own internal life. The veil is lifted most poignantly at the moment he leaves his family: “And he went in the taxi and as the car turned he looked and his eyes looked all sad and lost like a man who didn’t know what he was doing. He never even said goodbye or embraced me.” (p. 141) Two pages later, Adonis reveals that her mother later told her that her father had wanted for the family to move to Guyana with him, which suggests a more complicated story. It would have been interesting to hear his own perspective on his move.

The story of the marriage of Denis Williams and Catherine Hughes is, it appears, about two persons who may have loved each other passionately at one point but who could not live in each other’s worlds, and who were not even welcome there (and it had obviously been difficult for Williams to live, as an educated black man, in white, predominantly working-class Wales). But it is also a story of alienation and difference and the fraught search for the self within the “non-identities” (p. 121), as Adonis calls the condition, that had been created by colonialism. For Denis Williams, who had been raised in a middle-class Guyanese family as a classic “black Englishman,” this trajectory necessarily took him to Africa and then back to Guyana with a decolonial cultural mission, while for Catherine Hughes, this involved coming to terms with being Welsh, as part of another kind of British colony, and as the mother of a mixed-race family.

But ultimately, And: A Memoir of My Mother, is also an autobiography, of a woman, Isabel Williams, who chose to become known as Isabel Adonis, taking the surname of a black Guyanese grandmother she had never met (and whose first name was given to her at birth). While she is frank about the traumas of being different, and being labelled and regarded as different, the story also suggests that she has found power, meaning and a strong sense of self in the interstices of the various, elusive and contradictory worlds she has inhabited, being neither white nor black, being emphatically Welsh but also deeply connected to her Guyanese ancestry, and between the absence and presence of her father and mother. Her father may not have seen her, and may have been physically and emotionally absent from most of her life, but he is also a defining part of her, as she repeatedly acknowledges, as much as she challenges his patriarchal dominance. And that is a story with which many with similar histories, in the Caribbean and its diaspora, will certainly identify. It is recommended reading.

And: A Memoir of My Mother published by Black Bee Books and it is available in print and on Kindle.

A perceptive and lucid review of an outstanding memoir: thanks.

LikeLike