Here is the second part of my extended conversation with the Jamaican painter Phillip Thomas (part I can be found here), in which he talks about his work and issues and interests that have influenced him, and on which he has strong and at times very provocative views. It is long but well worth reading to the end, as Thomas talks in detail about his engagement with music, with some very interesting views expressed.

VP: You are a Senior Lecturer in Painting at the Edna Manley College. How important is teaching to your work as an artist and what, other than the professional affiliation and income, do you get out of it? What is it that you are seeking to impart to your students.

Teaching art is a very strange activity. When I was doing my post-grad fellowship, I was working on my Fellows exhibition at the New York Academy as well as being an assistant lecturer for Jenny Saville, Eric Fischl, and Vincent Desiderio. As working artists, they have figured out ways of meeting their own studio demands as well as giving their time and expertise to younger artists, both formally at the college and informally on their own time. Those lessons were simply invaluable and I was keen on doing the same in my own country.

I learned a lot about explaining aesthetic information to varying minds and abilities. It is a very difficult thing to do. Upon returning to Jamaica, I really had no intention of teaching formally. I was thoroughly busy with my own work and the idea of teaching would have been a distraction, to be honest. It was Petrona Morrison who told me that she would like to have my presence at the Edna Manley College, to expose students to another voice within the Painting department and the wider school. So I started on a part-time basis and began interacting with students.

Teaching challenges your ideas on a given subject and it allows for dialogue with the varying positions on the same. However, one easy error to make is the idea that teaching is one-directional. True exchange has to function both ways and it has to be a conversation with your students in order to have a better understanding of their position on their given ideas. That balancing act between teacher and student is an art form in itself. A lecturer like Omari Ra is a master at student engagement and he is so advanced at allowing the student to understand the sum total of their ideas. He has become a kind of benchmark for me in the idea of teaching art.

In the end, my responsibility as a lecturer is to allow my students to develop ideas and to challenge these ideas from as many angles as I can in order for that individual to have a full grasp of the subject and its potentialities. It is “easier” to impart art theory and history, since these are standards in art and practice, for the most part. Those foundational bits of information are only the first step in laying in a structure on which artists are better able to challenge the same structures and build anew.

The emotional aspect of teaching is something that I am more hesitant about. This is what I mean: when I was a student (sigh, I am getting to that age now when the “back in my day” becomes the go-to line), there was a more, let’s say, robust way of teaching and many of us as students developed harder skins because of it. Cecil Cooper alone would be a hard-enough task master to get by, and in my opinion we were better able to face the world. He was such a tough art teacher that his methods were considered too caustic for some. In this current period, there are so many psychological minefields to contend with and that gives me some pause in managing some students. I don’t have the answer to these problems, but when you are critiquing a student’s work and the student’s forearms are covered in scars, it gives me some hesitance in the delivery of my criticisms. Now, am I being sensitive to that student’s needs? Or am I under-preparing that student? I must admit, I don’t know and I won’t profess to know what the happy median is either. I am learning as I go, but there are major concerns for me as it relates to younger artists today.

Also, social media has created a whole new generation of professional student/artists – kids in school with professionally developed websites and social media platform pages etcetera. I am unsure as to how I feel about this kind of new way of “careering” before the “product”. Yes, I do know how romantic I sound, and how nostalgic these positions could be, but being on the ground and seeing the impact of student’s preoccupation with their career imaging, while failing in class, is frightening to me. I guess with every new advancement there are a set of Luddites complaining in the wings.

On a promising note, the “Rubis InPulse” project is a shining beacon that is doing important things at the high school level. As you know, myself and a few of the other artists from our community have participated in this art project for high schoolers. This gives us a chance to interface with students who are even younger and it gives us an opportunity to prepare the next batch of Edna Manley College students before they get to that institution. I can say with much certainty that this programme is delivering on its promises and we are seeing the results, and it is raising the stakes in art education.

VP: Jamaica has produced a strong generation of contemporary (representational) painters, in addition to yourself, this includes artists such as Khary Darby, Michael Elliot, Alicia Brown, Greg Bailey, Kimani Beckford, as well as younger artists such as Kevin McIntyre and Jordan Harrison, who you have taught. What is it that preoccupies these contemporary painters and what, if anything do they have in common? Why is there such a strong male bias in this group?

PT: The discipline of painting has been a longstanding practice in Jamaica, for many generations. We have seen a very broad spectrum of different kinds of paintings being made over the years and there have been several artists who have been very successful in executing these various forms. As I said earlier, there are different forms of figurative art and the ways in which we have come to understand these forms today are fundamentally different from the ways in which artists have understood them in the past. While I was a student in College there was a very small group of painters that was grappling with the language of picture making and coming to terms with the lack of technical education on the subject. So, for the most part it was a matter of experimentation, invention and approximation.

At that time, I really didn’t understand that my lecturers were educated as “Modernists” and that very position on the meaning of art is, in itself, consequential to the ways in which figurative painting would have been received. Amidst the Pollock and Mark Rothko knock-offs and the bands of Minimal and Colour Field works, we huddled through the self-conscious drips and splashes and talks of “happy accidents.” It is a strange thing to have graduated in 2003 and be fully trained in the art of Minimalism. In any period, there are those who survive and others who struggled. What I came to learn over that period is that lecturers cannot assert themselves as to what methods are proper and timely. It is a lecturer’s duty to help the student with his or her interests, not with their own. Thankfully much of that has changed.

Not all “painters” are created equal – I remember reading in one of your blogs on contemporary painting and the apparent male domination of this field in Jamaican art. Though I partially disagree, that sentiment is only part of a much bigger problem. What a lot of people in the art community don’t really understand is, in painting, we are not all held to the same standards, and separately from gender, class is a major factor in how artists are supported. Don’t think for a second that myself, Kimani Beckford or Alicia Brown could produce what a Khary Darby or a Michael Elliott produces and expect to be held within the same regard. There were so many gifted artists I studied with at the College that were not “to the manor born.” Folks like Mabusha Denis, Sheldon Blake, and Abbebe Payne, who were not given the same time of day as folks like a Khalil Dean and others. So, though your sentiment on gender is partial and gerrymandered, exclusion has more to do with class than with the mere issue of ability. Do remember that there is an entire generation of female academic painters that have held their own space in Jamaican art for a long time. In fact, one could argue that, with the exception of Barrington Watson, the majority of artists that were working in that language were women. From Gloria Escoffery to Roberta Stoddart.

As for the credibility of painting now, that is a very important question, and the foresight to quarantine the question to the Caribbean is also telling. I remember not too long ago Kehinde Wiley came to the Edna Manley College to give a talk and I found it particularly funny to see so many “Modernists” in attendance. In all seriousness, it was a bit strange. To think how difficult it has been to practice that kind of discipline at the very institution Wiley was now giving a talk. I remember thinking that we could have had so many artists who were more exposed to the rigours of picture-making at a much earlier stage in our “contemporary” art development. We are dualistic about these things and we pull no punches from the subject. It is easier to have an exhibition on digital art, as mere novelty material as opposed to a philosophical position on art, at the National Gallery of Jamaica than to have an exhibition chronicling the history of Jamaican painting. Yet everyone knows which of the two disciplines would have been thoroughly practiced in the history of our artistic development. Such an exhibition could be seminal in presenting an entire canon of thought in our country’s history. That’s how snubbed the subject really is, and as a result, the “painters” have to get in where they fit in.

Let me be very clear, I fully understand how archaic the basic understandings of painting can be in a space and time like this. And painting, by materialistic association, is often at risk of being heaped in a pile. The problem with this is that many underdeveloped new and multimedia works have slipped under the radar of criticism in Jamaican. I suspect that this is a disservice to those artists’ own development and the wider art community. The quest for basic “realism” in underdeveloped painting is usually the very extent of our criticism of painting as a practice. Unfortunately, such scrutiny has not been applied to the criticism of new media art and, by default, so many bad installations, god-awful videos and the like have been shuffled through the National Gallery, unnoticed…by some.

VP: You are an accomplished classical pianist and I know that you listen to classical music while painting. What is the relationship between your musical interests and your art? Classical music is often seen in a particular class context in the postcolonial Caribbean but what does it mean to you?

PT: The term “classical music” has all sorts of connotations to different people in different parts of the world and, of course, the Caribbean has its own special meaning and relationship to that tradition. Let’s start with the term itself. We often use the term “classical music” to mean, broadly, pre-20th century European music that follows a particular formal structure. However, the actual meaning, in musical terminology, refers to a period of music that sits between the baroque and Romantic musical traditions. These periods, in the same way the history of painting is conventionally structured, sit in relation to each other and their centres of influence often fluctuate, from culture to culture, period to period, and even between artists. Often times an innovation in instrumentation will change the manner in which composers write music or the ways in which instrumentalists will perform it. Case in point, the harpsichord that was created for Baroque music is in many ways a very different instrument to a modern piano, in the same way tempera paint is to oils. In fact, the invention of the pedal on the modern piano allowed for a “sfumato” like blending of musical tones in the very same way the invention of oil paints facilitated the same. Those bits of “improvements” and adjustments to artist’s instruments created openings for artists to push the possibilities in their craft, thus allowing artists to fully explore a wide range of potentialities for these new kinds of instruments and their use.

Like the history of painting, new technologies in other fields also affected music. The effect of the ability to record sound was comparable to the invention of photography, and both scientific innovations changed the ways in which the arts responded to these indispensable breakthroughs. Artists either embraced or loathed the proliferation of these devices and they also affected the ways in which the audience reacted to the “originals”.

Warfare was another human endeavour that affected how this or that painting or music was received, and in the case of music, one can imagine the revision that Richard Wagner’s compositions underwent as a result of WW2, many concert halls would not play Wagner’s music for many years because of the relationship it had to Nazi Germany and the Third Reich.

Outside of the inter-European issues that surrounded western music, the colonial fallout from music in different parts of the world was also important. Much of our very own musical arguments here in Jamaican, with regards to the importance of western musical traditions, can be seen in different parts of the world with different consequences. Let’s take Mao’s Cultural Revolution as one example. The Chinese, at that time, went through a period of musical nationalism that few former colonies on this side of the globe can imagine. The mass burning of western musical instruments, and sometimes their owners, was a bonfire of the vanities that only Girolamo Savonarola could rival. Here in the Caribbean, we have had those sorts of revolutions in one milder form or another, and there have been varying results across the countries in the region. The Anglophone countries certainly have a far more antithetical relationship to “classical” music than some of the other islands. Cuba on the other hand seems to have a very strong relationship to the classical arts than most of the colonized Caribbean.

The 20th century brought much change to music as it did everything else. The Romantic, post Romantic and “Atonal” musicians started to open the field of sound and, more importantly, other groups of musicians started to be heard by a broader audience. From Scott Joplin to Nina Simone, a wide range of classically trained instrumentalists began to inject other traditional sounds with rhythmic patterns and ideas about tone, composition and harmony. The Blues, Jazz and Soul became full counterbalances in the pantheon of musical expression and that gave rise to much of the current inter-relationship between the musical traditions. It was at that time issues of black racial politics became a subject in itself and black musicians began to think very carefully of how they would begin to repurpose instruments to convey what they were never designed to convey. The Mississippi Delta Blues traditions used sounds that were synonymous with the chain-gang songs, and the turbulences surrounding the Jim-Cow laws. One can only listen to Lightning Hopkins’ Black Cat Blues to understand some of the musical and lyrical codifications through which musicians expressed their concerns.

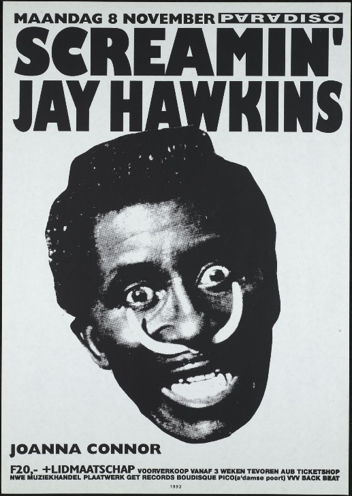

Nina Simone, in a BBC interview, once talked about her love for Johann Sebastian Bach, a Baroque musician (it is profoundly evident when you listen to My Baby Just Cares for Me – she moves so seamlessly between varying genres of music), and the ways in which many black musicians, who were thoroughly trained in classical music, had to abandon their study in order to survive. Andre Watts, who was perhaps one of the most accomplished black instrumentalist at the time, was largely unknown to black audiences the world over, and Nina Simone talked about so many musicians who were in that position who had to make those kinds of decisions because of the politics that surrounds the idea of a black maestro. There were others who were less fortunate, such as “Screaming” Jay Hawkins, who had incredible musical gifts but felt that he had to turn his gifts into a minstrel show because the windows of opportunity were so narrow (not unlike what is happening in the visual arts today). Incidentally, Hawkins’ 1956 classic I Put a Spell on You became one of Simone’s greatest hits, and if anyone does not know Hawkins’ version, I strongly suggest listening to both, in order to get the full irony of the Nina Simone cover. Without that prior information the meaning is lost. It is painfully clear to hear a rejected musicians’ sorrow in his lyric “I love you, I love you, I love you-anyhow and I don’t care if you don’t want me, I am yours…” The aforementioned Paul Robeson, on the other hand, became, not just the black voice of the twentieth century, but he was also considered to be one of the great voices of the era. Moreover, his political relationship to Russia and his contribution to, along with Nina Simone, the civil rights struggle became a large part of their battle with the US government, and one can listen to Paul’s resulting Congressional hearings of the late 1940s.

Speaking of the Cold War, it is well worth mentioning here that the concert halls were considered new battle-fields for world dominance. Van Cliburn, an American pianist, became a national hero because of his triumph on the Russian stage, challenging Russian musicians in Russian music. This became an impressive accomplishment for the Americans: the way Jesse Owens triumphed on the tracks of Germany or Bobby Fischer triumphed on the chess board (on the subject of chess, the first black grandmaster was a Jamaican named Maurice Ashley; it is sad that those achievements don’t fit the Jamaican “brand” and hence his invisibility – next up is Deborah Richards-Porter, dubbed “the queen of chess;” her title is now WIM, Women’s International Master).

Jamaica’s own history with music is also very interesting. Much of our class struggle gets presented in musical taste. The idea that this or that kind of music is for this or that kind of person has been an ongoing debate. Whenever the argument for or against the Noise Abatement Act is being discussed, the struggles about musical taste are never far behind. One example of our “entanglement” with culture and their respective musical traditions can be found in the musical score of Jamaica’s national song pledge. The English composer Gustav Holst composed one of his most celebrated works titled The Planets in 1914. The planets are an “ethereal” composition on the celestial bodies and many composers were known to use this theme with varying interpretations. Perhaps the most famous of the planetary compositions can be heard in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey, and of course I am referring to Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra – Sunrise. However, the score that concerns us is Holst’s composition titled Jupiter. It is from this composition our National Pledge’s melody comes, but very few are aware of that. There is a generation of Jamaicans who remember the “romantic” era of the Ward Theatre or the early days of the Carib Theatre. I will often hear Jamaicans of that generation lamenting about seeing Arthur Rubinstein or Nina Simone performing here in Kingston. It’s a bit hard for my generation to even imagine those performances, or worse yet, to know or even care who those musicians are. As it stands now, we often get weekly papers or social media updates that are littered with articles on music or the lack of it. About what constitutes noise, or disturbance, and what should be considered music, even though I would imagine that a person playing Gustav Mahler’s Titan at full decibel at 2 am would be considered noise… but that’s just me.

This argument on “noise and the law” naturally spills over into politics, and politics in Jamaica is also a battlefield for the classes. Politicians often employ Dancehall music for their various rallies and political meetings, while ensuring that their own children keep up with their violin and ballet lessons. The same goes for the political motorcades and the sort of music that is being used then, providing that those motorcades drive through the right neighbourhoods. There was a slew of criticisms from Opposition member Peter Bunting that I found so very funny; it had to do with the new Minister of Finance Dr Nigel Clarke. Apparently, Dr Clarke was seen as an elitist because of his taste or ideas about the sorts of music he enjoys listening to. It became such a spectacle that there was a letter to the editor in our Jamaica Gleaner, published March 9, 2018 titled, “So what if Nigel Clarke likes classical music?” The irony is that part of the selling pitch for the PNP’s Michael Manley and his family, during his tenure, was the fact that he was presented as having “taste” in music and all things “culture” and in so many of the documentaries on the Manleys, it was very evident that those ideas about taste were hailed as the evidence for the capability of good governance. What was painfully clear is that difference in the supposed race of both men was the unsaid thing with regards to how this question of “taste” was interpreted and responded to.

Of course, post-independent Jamaica didn’t simply seek to break away from Britain, politically; more importantly, we embarked on the quest for self-reflection and re-establishment of our identity. Music became one wing of that new identity and it is still, perhaps, our most popular commodity, even though it may not be our most sober one – at times. The religion of Rastafarianism, like all other religions, has its own set of musical beliefs. Consequentially, Rastafarian music has several types of musical structures because of the importance of drumming and its timing in its overall syncopation. There are traces throughout Rastafarian music of musical traditions going back to the polyrhythmic drum systems of west Africa. In the same way, Black-American music went through several stages throughout the twentieth century, much of our popular music here in Jamaica went through a sort of “renaissance,” more so in the latter half of the twentieth century.

mixed media installation , variable dimensions)

With the influence of Burru, Kumina and other drumming languages, Reggae music became a kind of composite of the idea of African music that was “disembodied” from the continent and lives here in the spirit of the people, and each island developed its own form, some less popular than others. An important point to make here, as it relates to instrumentation is that one primary difference between the Caribbean and the other major musical traditions, in North America and other regions, is the invention of instruments due to the “make-do-with” culture that comes out of slavery, de-industrialization and the catastrophe of the concept of the Third World. From kitchen utensils to oil drums that were forged into steel-pans, the Caribbean had to figure out ways to craft a sound that did not exist before, primarily because the conditions did not exist before, and out of these specific structures came an unmistakable sound that could only exist in the region.

One very important song and rhythm to me, at the core of my appreciation for our music, is the Abyssinians’ Satta Massagana. It is very difficult to explain, precisely, how importantly this piece of music is composed structurally, conceptually and more importantly emotionally. Part of the reason I enjoy Everald Browns’ instruments so much is because it is Satta Massagana personified. It does speak to me of “a land far away.” Of course, that rhythm is the “Sankofa” of our modern and contemporary musical tradition. It is used by many other musicians here in Jamaica, most notably Sizzla Kalonji. His Positively Clear, like Satta Massagana, also speaks of repatriation, not simply of the body, but of the mind.

However, before we get into Sizzla, it is worth mentioning here, the late 70s and early 80s, the birth of Dancehall, Hip-Hop and Rap. In order to understand these genres of music, we must firstly understand the conditions of politics and entertainment in Jamaica. The “sound system” became a new kind of instrument at that time and it was often used as an outlet for espousing various political ideas. Sound system selectors were notoriously political then and there were many sound systems that were considered JLP or PNP Sound Systems. In fact, both former Prime Ministers Edward Seaga and P.J. Patterson were heavily involved in inner-city music and its production and, for the most part, I suspect that it is for some of these reasons that Jamaican politics and its music are so intertwined. Let us start with the idea of the “sound clash”. Some of the earliest rivalries between musicians can be heard between people like Prince Buster and Derrick Morgan. Though, technically speaking, these musicians were not Dancehall musicians, they started one of the fiercest rivalries in music at that time and it became the template for dancehall musical rivalry today. It is important to understand that rivalry in the age of post-independent nationalism meant that the way you challenged your opponent was on his merits in national pride. Hence, Prince Buster’s 1963 hit Black Head Chinaman was a stinging critique of Derrick Morgan to which Morgan responded with a song titled Blazing Fire and, as far as I can tell, this is the first time I have ever heard the everlasting sentiment “bad-mind” in Jamaican music – a sentiment that is still with us today. Funny enough, Morgan starts his response song with a few “Chinese” words; this went on between them for a long time and to legendary proportions. Remnants of that can be found today in the clashes between sound system selectors such as Mighty Crown (a Japanese sound system), Black Chiney, and Tony Matterhorn, who will often discuss racism within the new influx of Asian Dancehall queens and sound systems.

Many Credit Daddy U-Roy with the invention of the modern Jamaican DJ. Even though, internationally, the term DJ meant Disc Jockey, it has evolved to mean performing “Artiste” (or “Artist,” take your pick). U-Roy was perhaps one of the first people to have the first five spots on the top 10 charts in Jamaica and he would often replace music with other music before the first had ran its cycle. It is a similar practice that artists, notably Vybz Kartel, use nowadays.

However, back to Nationalism. Musicians at that time were very keen on their sense of nationhood and there were artists who were not following those principles. We must understand that Jamaica was coming out of two anti-Chinese riots. Yellow Man (ironically enough) made two important songs to this point. Firstly, he made Mr Chin, a 1982 track which was banned from the airwaves. The song talked about the haberdashery practices that dominate downtown Kingston. After the song was banned, Yellow Man made another song titled Mr Wong and, in his opening “query,” Yellow Man questions why his original song was banned. Apart from nationalism, vulgarity and explicit sexuality were there from the inception of early dancehall. Perhaps the earliest and the raunchiest was Prince Buster’s Big Five (and please, when you all listen to this song keep out of reach of children). “Big Five” was a popular Go-Go club/Motel in Cross Roads at that time and Prince Buster made an “homage” to both the male and female genitalia in this song, a “tradition” that carries on to this day.

Like Dancehall music, hip hop and rap had their own pioneers as well, and much of them are the same as ours. However, unlike the Caribbean, Black American culture was not directly considered “third world.” Their predicaments were profoundly different, in that, they were experiencing some of our conditions and disenfranchisement in the midst of white American wealth, freedom and grand liberation. Also, Jamaican musicians did experience some of the sort of consistent plagiarism that black American musicians experience. Many of the “Rock n Roll Gods” of white American music sourced their entire oeuvre from “unknown musicians” in black American and some of our Jamaican culture. There was a natural kinship between Hip-Hop and Dancehall and many Hip-Hop musicians are in fact Jamaicans themselves or descendants. Those issues were beautifully critiqued in Mos Def’s song titled Rock N Roll from his 1999 album Black on Both Sides (highly recommended).

In any aesthetic practice success can often place a kind of unexpected burden on the artist, genre or era of that discipline, and both of these music groups were subjected to these forces. When packaging, as opposed to information and talent, becomes the driving force behind what gets played on the airways or hung in the gallery the thing that suffers the most is the work of art and its potential audiences. Both Hip Hop/ Rap and Dancehall are old enough as genres to be in a position to talk about the “good old days,” even if they weren’t all that good. There are countless interviews of musicians on both sides who have been on the ground floor of their respected music discussing where their genres have failed and something cataclysmic seems to have happened in the recent past. It is not hard to find interviews of Bounty Killer or Jay-Z talking about “when I was coming up.” This shift apparently occurred in “Generation Z” or “Gen Z” for short. A new type of angst that has occurred due to the rise of social media and the global village. The concept of the “Digital Native” has presented new forms of “anarchy” that previous generations have not anticipated, and it is clear in the music. Both “Trap-Rap” and “Trap-Dancehall” glorify heavy drugs and suicide like no generation of black music has ever seen. Without even mentioning the rate of drug overdose and suicide, a phenomenon that used to occur primarily in white rock bands, has become fodder for contemporary black musicians. The prevalence of mass murder, emptiness, loneliness and hopelessness in the midst of a technological revolution is perhaps one of the greatest ironies in the twenty-first century. A great example of this kind of new black music is Desiigner’s 2016 song Timmy Turner.

Perhaps, Timmy Turner is one of the most ominous works that have come out of the genre in this period. There is a chilling recurring kind of “Gregorian Chant” as the primary melodic structure of the tune that reminds me of a “requiem.” Desiigner then proceeds to tell us what he regards as the true feelings of a popular cartoon titled “Timmy Turner,” who is depicted as a very young white boy. However, Desiigner lets us know that Timmy Tuner is really desirous of committing mass murder in a Columbine style manner. The lyric reads “Timmy-Timmy-Timmy Tuner, he was wishin’ for a burner (gun), to kill everybody walking, he knows that his soul in the furnace….” It is true that some of the early blues musicians such as Robert Johnson and his 1938 song Me and the Devil Blues did a similar “crossover”, but even then such did not become standard lyrics. This sort of music is a part of a new wave of Rap musicians that has been dubbed “Mumble Rap” because it is very difficult to hear exactly what is being said in these works. The tone mimics a drug induced “incoherence” that was not previously considered part of the subject matter of these kinds of black music. In fact, in Dancehall music, there used to be very little tolerance for cocaine, pill or “lean” usurers, and Deejays would often express in their songs their intolerance for any narcotic outside of ganja.

Like Hip Hop music, Dancehall music is diversifying. American “urban” music has always carried a variation of languages, styles, rhythmic patterns and choice of instrumentation. Southern Rap, for instance, because of early migration patterns, has a very strong Caribbean presence and marching bands and carnivals have been a part of their sounds as a result. They have always boasted a very heavy “brass” section in their instruments and it is very evident in works such as Ludacris’ Move B@tch, Get Out the Way. Also, Southern language is very much a part of the music. The ways they have pronounced words and phrases have been a part of the tapestry of their sound. To this day. I am still trying to decode some of the words to James Brown’s songs. Jamaican music has also “diversified” in recent times. Montego Bay has become a second centre for music in Jamaica. There was a time when all Dancehall musicians wanted to be from Kingston, and particularly working-class Kingston; however, that has now changed and artists from other parts of the country and demographics are proud of their particular region. Such as the differences between East and West Coast Rap, these inter Jamaican language differences have found its way into contemporary Dancehall music. One can hear these linguistic differences between the ways in which words are pronounced and even the kinds of criminalities that are referred to in those kinds of music forms. All these issues and developments are important to the ideas I express in my own work.

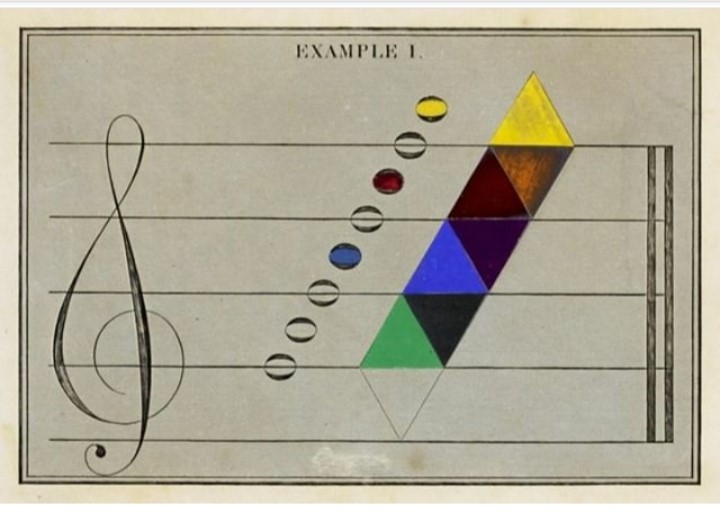

As for my own tastes, I enjoy what is good in all forms of music. Music is a second love for me and it is something that I took the time out to begin to study. I do remember the days of trying to do the Associate Board of the Royal School of Music (ABRSM) examinations and balancing a visual arts practice, and with the exception of Arnold Schoenberg, I am unsure if it is at all possible to manage both (lol). The saving grace for me, were music is concerned, is that I have absolutely no intention of performing it. My enquiry in its discipline is just for my own internal interests. I do listen to music while I work and my taste can encompass both Franz Liszt and Fela Kuti. Music is an interesting window into other worlds, and visual artists certainly have used the power of music to facilitate some ideas about the formalities of visual arts – not unlike Wassily Kandinsky or Everald Brown, many artists over the centuries have, to one degree or another, used synesthetic ideas about the correlation between both senses and those interdisciplinary ideas about visual arts can be very fruitful.