Some works of art reveal their content easily. Others challenge the viewer, and sometimes also the artist, to the point of resisting explanation. This is not a popular approach these days, in a context where easy artistic legibility is promoted by some, populistically, as a necessary condition for democratizing the arts, and artistic opacity dismissed as elitist and undesirable. There however needs to be room in art for the poetic and political implications of opacity, as this is, for many reasons, fertile artistic territory. In fact, sometimes it is art’s very point.

The body of work presented in Petrona Morrison’s current exhibition, New Works, does not read easily, at least not at first sight. Having spent some time engaging with visitors, at the opening and in the exhibition since then, I can see that some are non-plussed at first. It does not help that the exhibition consists of work created and produced in digital media, and mounted without the usual legitimizing trappings, such as picture frames. Or that it furthermore involves photographs produced by the artist as well as found images and objects, as these challenge common notions of exclusive artistic authorship. Or, even, that there is no price list.

The latter is worth noting because to many in the Jamaican context, an art exhibition is first and foremost a sale, and art is validated primarily by its standing in the art market. The Petrona Morrison exhibition was deliberately not conceived as a sale; it is first and foremost an exhibition, as a way of displaying and sharing with various audiences a cohesive and immersive body of work, as a communicative act. It is not that there is anything inherently wrong with selling art, or with producing and promoting it for sale, but it is problematic and very reductive when serving as a luxury commodity becomes art’s sole purpose, and its primary method of consumption and validation. There must be room for other approaches, and alternative artistic economies, if we are to have a healthy, diverse and dynamic art ecology. This exhibition is thus also, by implication, about (re-)claiming space for different types of contemporary art, at a time when the terrain for contemporary art appears to be contracting in Jamaica, and about asserting the validity and importance of those artistic approaches that do not conform to dominant expectations.

To return to the question of opacity, and the apprehension this causes in many viewers: in Petrona Morrison’s exhibition this usually dissipates quickly when visitors are engaged in conversation with the artist or myself, although these conversations merely provide some insights, a point of entry, and not the definitive explanation some may have expected. While it takes some effort to unpack it, and a willingness to accept that not everything can be explained, the content of the exhibition is actually quite relatable, as much of it is couched in current debates and relevant to the personal experiences of many visitors. Many stimulating conversations have already been had in the exhibition and it is a pleasure to see visitors opening up about how the exhibition speaks to them, with significant room for personal interpretation. Chances are that this would not have happened if the art works on view delivered their content in a more obvious and prescribed way.

The body of work presented in this exhibition follows and builds on a previous project by Petrona Morrison in which she explored the cultural and political implications of the “selfie,” and the various (self-)imposed conventions and acts of staging and self-fashioning involved. This time around, the point of departure was the recent debate about NIDS, Jamaica’s proposed national ID system and the accompanying draft legislation, which among other provided for collecting blood samples, DNA, and vein and skin prints, as possible means of recording and identifying individuals, far beyond the customary biodata and photographs. Much of the controversy revolved around privacy rights, and the draconian proposed penalties and denial of state services for those who failed, or did not wish to become part of this system.

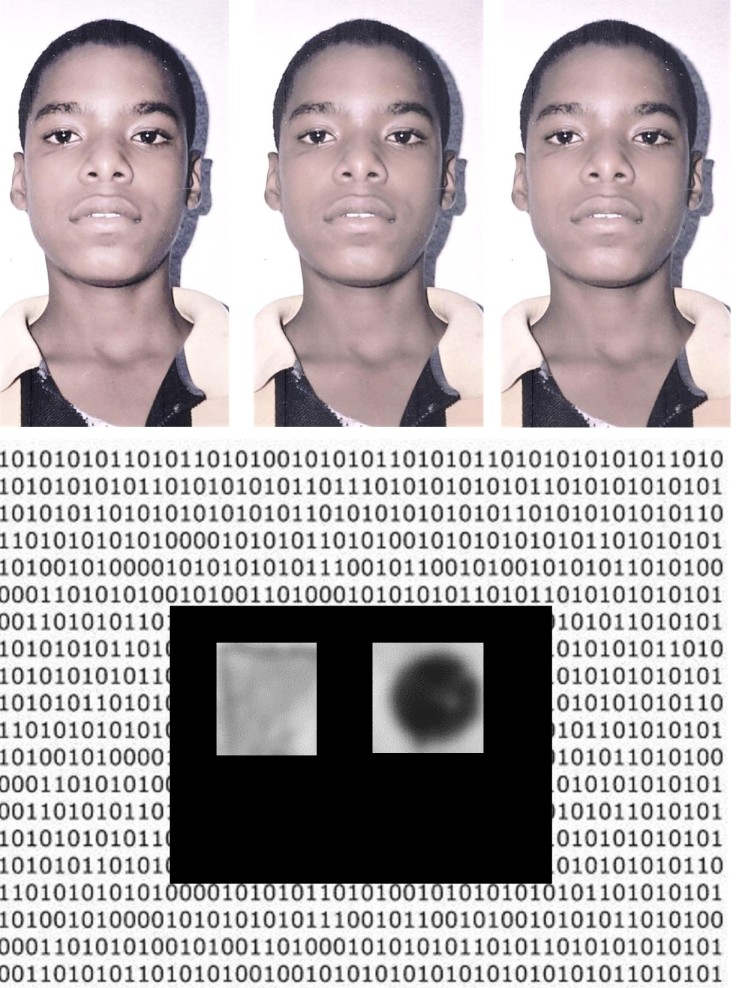

A key question explored by Petrona Morrison’s recent work is how we are positioned and perceived by our representations, those we create ourselves and those that are captured or imposed by others and by society – from the conventional ones, such as the photographic (self-)portrait, to those images that delve into the microscopic inner structures of our DNA or, on a macro-level, our position in the social and physical environment. Some of the works in the exhibition include actual portraits, but all are “portraits” in a broader sense. They engage with, to borrow a term which has gained currency in Caribbean literature recently, the cartographies of contemporary life, with how societies and systems survey, interpret, and locate individuals and social groups, and with how individuals, in turn, navigate that terrain and the perceptions that result from it, while negotiating their own sense of self.

One of the challenges of contemporary life is the manner in which lives and identities are turned into data, often forcibly, with the lack of room for complexity, nuance, and refusal that comes with that. That being “mapped” in this way also amounts to being “owned” is an important consideration in the postcolonial Caribbean, given the histories of surveying and mapping, slave ledgers, evolutionary classifications and racial “castas,” and related technologies of conquest, ownership, segregation, and control to which the region has been subjected, historically and in the present. In this context, being unmappable and unknowable, and defying systems of classification and social management, can be regarded as necessary acts of resistance, a practice of socio-cultural marronage which lives on in the contemporary era.

The emotions that have surrounded the NIDS debate here in Jamaica, and the more recent controversies about certain local high schools introducing biometric data collection methods, illustrate that this resistance runs deep in Caribbean culture. The association between coercive, disciplinary power and the panoptic gaze, to reference the French philosopher Michel Foucault, is well understood here. As a result, it is very difficult to convince persons that the threats, actual and perceived, posed by technologies such as satellite and drone surveillance, biometric controls, and DNA mapping may be outweighed by their advantages, such as enhanced security or the access to valuable medical information.

Such considerations are also active in Petrona Morrison’s art. Those who know her are aware of her strong, well-read intellect and capacity for incisive, well-structured analysis, generally and in the field of art, but her own artistic process is highly intuitive, often taking on a life of its own that defies explanation even to herself, revealing itself only after the work has been completed. She has always been weary of having her work “explained,” and of being asked to do so, as this is inevitably a reductive process that puts the work, and the artist, at risk of being pigeonholed, and she prefers for any interpretation to be open-ended. This is an inherent part of her work, and directly relates to the broader socio-cultural politics of opacity and refusal that were described earlier on.

While Petrona Morrison has worked primarily in digital media for more than a decade now, many visitors to the exhibition have expressed surprise, as if her use of digital photographic media represents a new direction, even though she starting on this path some two decades ago, when she started incorporating X-rays, topographical images and maps in her installations. One reason is that she has not had a solo exhibition for many years – in Jamaica, her most recent one was in 1991, at the now defunct Makonde Gallery, while her most recent solo exhibition was at 198 Gallery in London in 2005. While she has exhibited various works in digital media at the National Gallery of Jamaica, in exhibitions such as Curators Eye I, the National Biennials and the Jamaica Biennials, Jamaican audiences have not seen a comprehensive body of her work for some twenty-eight years and the changes in its direction may not have been obvious to all as a result.

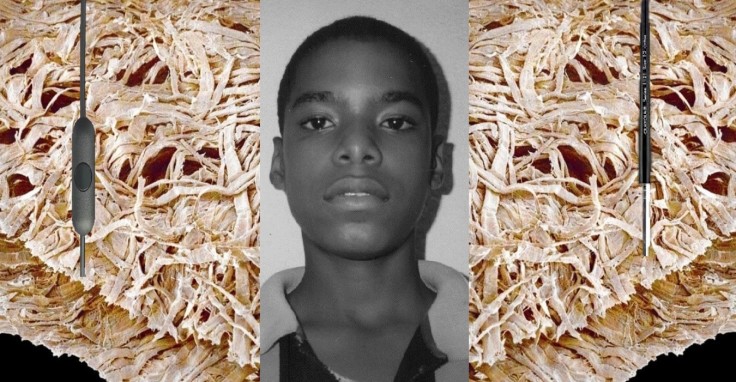

Petrona Morrison’s current work may seem dramatically different from the strongly material, textural assemblages she exhibited in 1991, and the large-scale, found object constructions and installations that followed after that, but there are important continuities in the digital photo-collages. Formally, for instance, there is a shared stark, rectilinear organization to her compositions, which she attributes to her ongoing interest in the formal rigour of African art (she has in the past cited Dogon architecture and the carved doors she saw in Mombasa as sources). The surreal manner in which the represented objects are placed against their backgrounds in the digital images is, furthermore, not substantially different from what she did with actual found objects in her earlier work, and mines the visual and symbolic potential of these placements and juxtapositions. The Archives installation, one of the key works in the current exhibition, is perhaps most revealing in that regard, as it involves actual objects, combined with digital images, and has some of the ritualistic qualities and altar-like format of her installations of the mid-1990s.

It is harder to substantiate the thematic continuities in Petrona Morrison’s work but they are also present. The work from the 1990s she is best known for, spoke about healing, renewal and reconnection, in the context of the African Diaspora and at a personal level. There were always implied references to the body, and specifically the black body, which were abstracted earlier on but have become more specific and recognizable. A major turning point in that regard was the room-sized installation, Reality/Representation (2004), which was produced for the Curator’s Eye I exhibition at the National Gallery of Jamaica. In this installation, the central image was a photographic portrait of Petrona herself, segmented and vertically arranged to become a giant totemic form.

While she now uses male and female models, particular attention is paid to the black male figure/body, as the bearer of some of the most burdensome and destructive social perceptions. Some images are anonymous and abstracted, with the figure seen from the back or only partially, but in such a close-up view that there is also an uncomfortable sense of proximity and intimacy – an inescapable confrontation with what the black male body invokes and represents. Others are haunting portraits of specific individuals. The portrait of a young man that reappears in several of the recent works, which was taken years ago with a rudimentary phone camera, is particularly poignant, as it juxtaposes the softness and vulnerability of youth, which in itself suggests untold stories, with the problematic, generalizing assumptions that are often made about young black men like him.

The Archives installation includes a small self-portrait of Petrona Morrison and this is only the second such self-portrait in her mature work. Small and seemingly hesitant as it is, with the face partially obscured by tissue, it is a significant and revealing presence, because Petrona Morrison’s work has always had an important autobiographical subtext, which draws from her personal and medical history, and her own location within the social dynamics and issues of representation her work speaks about. In many ways, the work has always been about herself. This is perhaps the most significant area of continuity over the years, and across media, but it is also the aspect of her work that is most deliberately opaque, with the veil of privacy only rarely lifted. Reality/Representation was the first work where that was done, and it represented a powerful and revealing coda to her earlier installations, but the body of work now presented also builds on that moment, not only because of the inclusion of a self-portrait, but also because of the shared engagement with questions of representation and the mapping of the human body. While it may not be as visually evident as in Reality/Representation, this is perhaps the exhibition in which she is most expressly and personally present.

nice

LikeLike