On a recent visit to Belgium, I visited several art museums: the Groeninge, Old St Jan, Folklore and Lace Centrum museums in Bruges; the Mu.ZEE in Oostende; the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp; and the Magritte Museum and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts (Old Masters). This is the first of a four-part report on these museum visits.

One reason for going on this museum tour was to reacquaint myself with my Belgian artistic heritage. This heritage often seems far removed from what I deal with professionally here in the Caribbean, but it remains an important part of my own cultural, education and personal foundations and there are in fact some surprising connections. The tour was also an opportunity to look at any new developments in Belgian museums, a topic to which I will return in the other parts of this report. I also wanted to see the exhibitions on the legacies of James Ensor (1860-1949) that are currently on view in Oostende and Antwerp, as 2024 has been declared as the Ensor Year, to mark the 75th anniversary of his death, with several more exhibitions and related events being planned for later in the year.

James Ensor, who is one of my favorite artists, is an important figure in Belgium’s eccentric but influential contributions to European modernism. Oostende, where he lived, was the main harbor city on the Belgian North Sea coast at that time and an emerging coastal resort. The moody North Sea was a major inspiration to his early work, as were the interiors of the Oostende bourgeoisie, to which Ensor’s family belonged. Initially related to realism and impressionism, his work soon became more idiosyncratic, with grotesque, fantastic imagery that drew on local carnival traditions. That too was inspired by his immediate environment, as his family operated a curiosity and souvenir shop where carnival masks were sold. The paintings, drawings and prints he produced in the late 1880s and early 1890s are regarded as his major works and present a poignant, subversive satirical portrait of the tumultuous social landscape of the Belle Époque in Belgium and his own travails as an artist in that context. Ensor’s work was also formally innovative and his non-conformist, sensualist engagement with paint, pigment and color prefigures later developments in modern art, such as abstract expressionism.

These formal and thematic developments were on full display in Rose, Rose, Rose à Mes Yeux at the Mu.ZEE in Oostende, a gem of an exhibition which I thoroughly enjoyed and learned a lot from. Ensor’s consistent engagement with still life painting served as the core of this exhibition, contextualized in a broader overview of the genre in Belgian art from 1830 to 1930. That Ensor would have revisited the still life throughout his career should not surprise us, as the genre lends itself well to symbolist and surrealist approaches. The exhibition features some fifty works by Ensor and many others by well-known and not so well-known Belgian artists. It was instructive to see the connections with other artists, for instance in his use of Chinoiseries (fantasy orientalist imagery), as well as the ways in which Ensor departed from the norm as his work matured, redefining the genre in the process. Roses (1892), a veritable explosion of lush pinks, blues and purples that goes well beyond conventional still life, illustrates how the still life served as an occasion for formal explorations. Other examples illustrate the genesis and development of Ensor’s fantastic imagery. The Skate (1892) may at first seem like a conventional realist still life with fish, but the sea creatures take on humanoid and even erotic qualities that add a surrealist dimension.

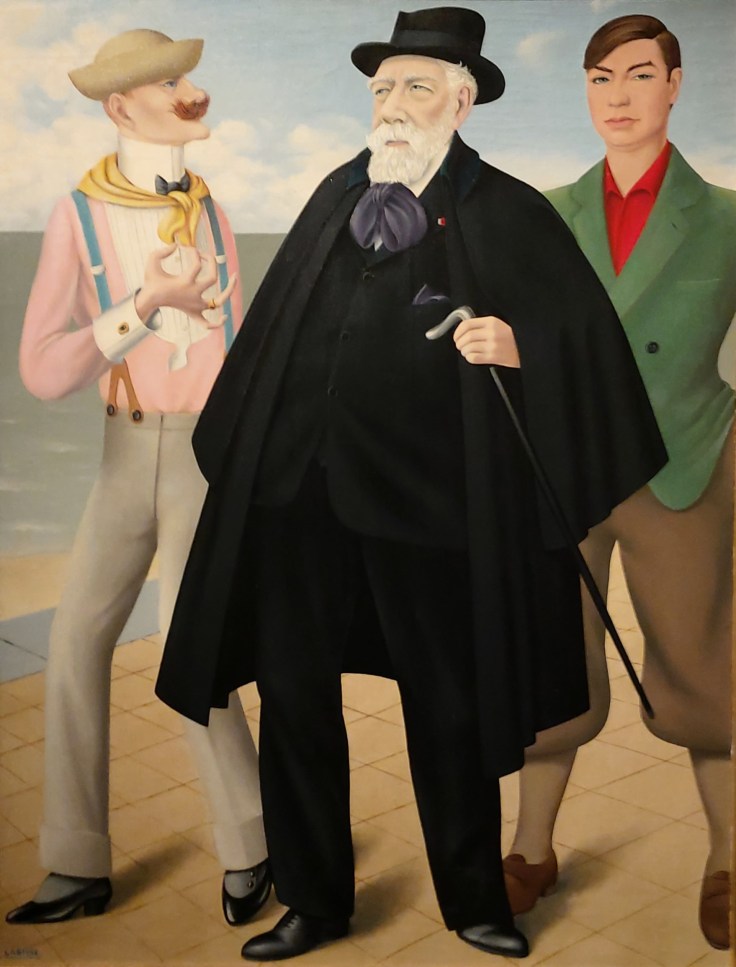

To accommodate this exhibition, a smaller gallery space was constructed in the middle of a larger gallery and most of Ensor’s still lifes were concentrated there, with comparative works in the space around it, and adjoining galleries. I did not care for the architect-designed structures, with the deliberately rough, semi-open carpentry of the walls, which was visually distracting, and the uncomfortable “cubist” wooden gallery benches, which seemed out of sync with the work on display. Mounting the works closely together in the central gallery however echoed the way in which they would originally have been displayed and seen in nineteenth century bourgeois interior and period exhibitions, and allowed for close-up viewing and comparisons that would not have been possible with a more conventional, spaced-out installation. Several other Ensor works were also on view in the permanent galleries of the museum and one work by another artist, Bonjour Monsieur Ensor (1964), by the French surrealist painter Felix Labisse (who also lived in Oostende), spoke to Ensor’s status as a celebrated public figure later in life.

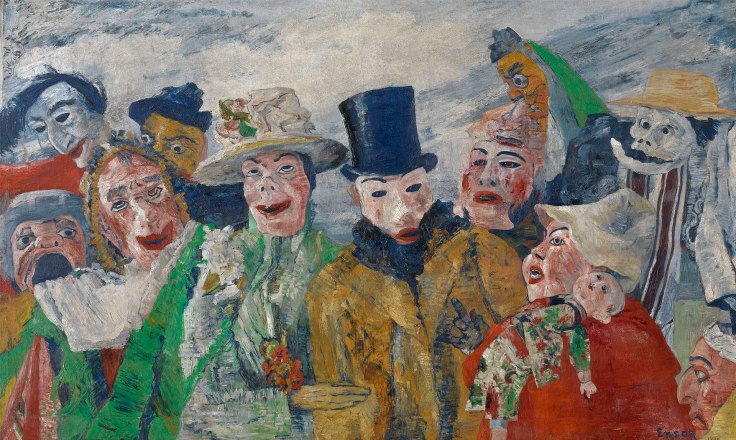

I also saw a small exhibition of Ensor works at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, which has the largest collection of his work. It featured key works such as The Oyster Eater (1882), one of his early interiors; Skeletons Fighting over a Hanged Man (1891), in which the fighting skeletons allude to the art critics who routinely savaged his work; and The Intrigue (1890), a group of grotesque masked figures that make us wonder whether the masks reveal their true character. It was not the ambitious, impactful, and well-curated and -contextualized Ensor exhibition I had hoped to see at Antwerp, so I was admittedly disappointed. However, it turned out that what I saw was just the preliminary for what is billed as the largest exhibition ever of Ensor’s work, Ensor’s Wildest Dreams, which is scheduled to open in September. I may have to travel back to Belgium to see it, as this exhibition sounds like a once in a lifetime experience.

I was very disappointed to hear, however, that Ensor’s The Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889 (1888), a crucially important mural-size painting in his oeuvre, will not be in Ensor’s Wildest Dreams. I understand that its loan was requested from the Getty Museum in California, which now owns the painting, but apparently declined with the size and fragility of the work cited as the reasons. The Entry of Christ into Brussels work should never have left Belgium. It had been privately owned but on loan to the Antwerp Museum for several decades. Its owner controversially sold the painting to the Getty Museum in 1987, where it was restored and is now on permanent view. Questions of cultural ownership and museum ethics arise here, as this work is an important part of Belgium’s artistic patrimony.

The Entry of Christ into Brussels spoofs the religious theme of the Entry of Christ into Jerusalem. It represents an unsparing carnivalesque satire of Belgian Belle Époque life, in which the forces of social change and conformity contend and in which the artist appears as a martyred revealer of uncomfortable social, cultural, and artistic truths. Belgium’s controversial King Leopold II, of the Congo Free State’s genocidal infamy, features in the painting, as a uniformed, excessively decorated carnival character, just below the central Ensor/Christ figure, almost as if they are antipodes. It is not the only work in which Ensor satirized Leopold II: in his drawing Belgium in the 19th Century (1989), for instance, he appears as a clueless godlike figure in the heavens, who is wondering what the fuss is about and appealing for patience, while a bloody revolution is raging on the earthly plane below.

Ensor helped to lay the foundations of surrealism, expressionism, and social satire in modern art in ways which have also resonated here in the Caribbean. The influence of his expressionist painting style and grotesque imagery was, for instance, palpable in the work of Milton George (1939-2008) and the other neo-expressionist painters who dominated the Jamaican art scene in the 1980s, such as the young Omari Ra (b1960). This is perhaps most evident in Milton’s Opening Night (1978), which lampoons the social pretenses of the art world with two grotesquely masked figures conversing at an exhibition opening.

This article was first published in the Monitor Tribune, a Jamaican weekly. It is reproduced here with a few minor changes.