This article originally appeared in two parts in the Monitor Tribune.

Part 1

Recently, I travelled to the Cayman Islands for several professional projects. One of these was the exhibition 81° West: Cartographic Explorations in Contemporary Caymanian Art, which opened on October 6 at the National Gallery of the Cayman Islands (NGCI). The exhibition was conceived by William Helfrecht, the NGCI’s Curator of Collections, who was also its curatorial lead, and co-curated with Director and Chief Curator, Natalie Urquhart, with support from Daniela Granados as the curatorial assistant. I came to the project rather late, as curatorial consultant. Naturally, given my professional involvement in this project, I cannot present an independent review here, but the exhibition is of broader interest to the Caribbean, hence my decision to dedicate this week’s column to it.

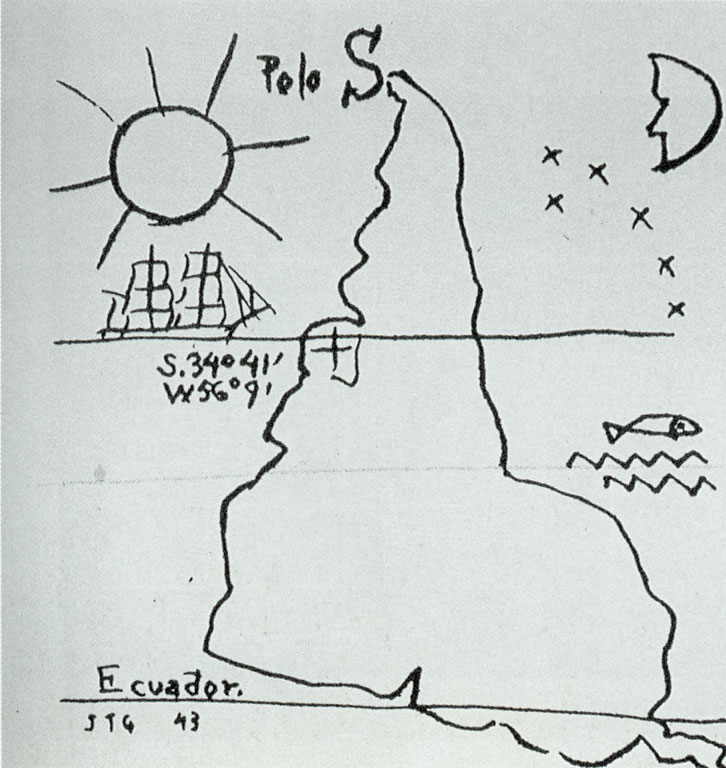

Maps represent our three-dimensional world in a two-dimensional diagrammatic form (although maps can be three-dimensional, for instance as a globe), for purposes of wayfinding and oversight, using technical and representational conventions that are as revealing as they are ingenious. The Mercator map projection, which is still commonly used today, notoriously puts Europe at its center and significantly underrepresents the size of the continents of the Global South in the process. It embodies the very concept of Eurocentricity. Such ideological biases of maps have been a regular subject in modern and contemporary art, perhaps most poignantly in América Invertida (1943), the “upside-down” map of South America by the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García, which puts into question the global dominance of the Global North, and particularly the USA in the American continent.

The modern science and technology of cartography evolved hand in hand with European exploration and colonization, and Euro-American imperialism (although other cultures have of course also produced maps and alternative forms of mapping and wayfinding exist such as the Songlines of Aboriginal Australia). Early colonial maps, more obviously so than more recent incarnations, vividly illustrate the underlying ideologies and biases, and illustrate how mapping the world became synonymous with taking possession. As William Helfrecht wrote in one of the text panels for the exhibition, “in the Renaissance and Enlightenment age, to be charted was to be both formally recognised and symbolically summoned into existence.” From the perspective of the European explorers and colonizers, the uncharted parts of the globe were indeed “terra nullius,” empty lands waiting to be discovered and claimed.

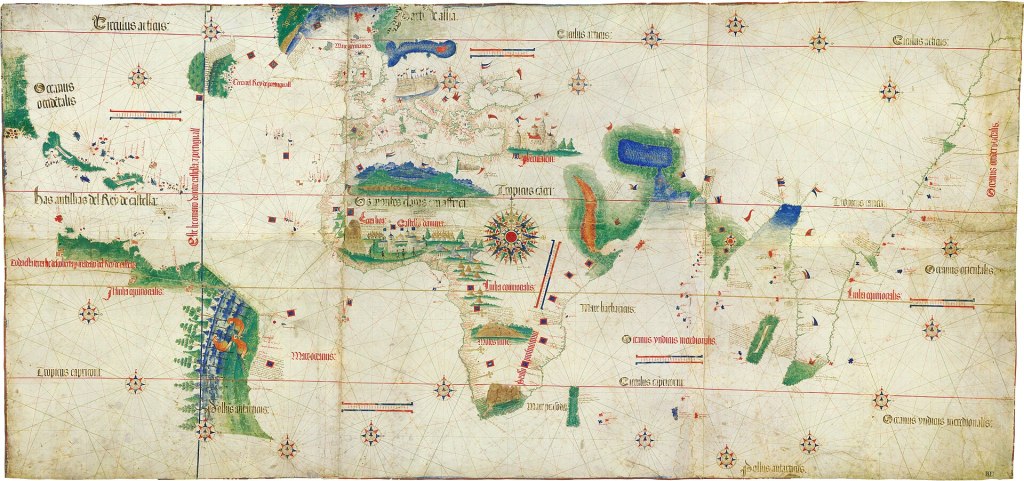

Maps, in their conventional form, are indeed not only a way of representing the world, but also of imagining and ordering it, speaking to socio-economic and cultural hierarchies, political power relationships, and conceptions of ownership and control in the process. Despite this historical baggage, maps can also be extraordinarily beautiful and resonant, and some are remarkable works of art. This is well illustrated by the Cantino Planisphere, a Portuguese manuscript map on parchment from 1502 (of which a facsimile is on view in 81° West). This map is an artistic and technological marvel, as the earliest surviving nautical chart and “global” map based on astronomically observed latitudes. It not only speaks to the rapid development of modern navigational and cartographic technology, at a time the European conquest of the rest of the world had just started in earnest, but indirectly it also speaks to the Spanish-Portuguese rivalries during the Conquest era, and of European “discovery” timelines other than those recorded in Columbus’ diaries. The Caribbean is represented on it, and deferentially labelled as “The Antilles of the Castilian King” but, as was noted by my Caymanian colleagues, there are three small islands west of Jamaica that may well be the Cayman Islands. This puts Cayman on the cartographic record one year before Columbus first sighted Little Cayman and Cayman Brac on May 10, 1503, and christened the islands Las Tortugas, because of the prevalence of sea turtles in its waters. It appears that some European explorer, on Columbus’ armada or otherwise, had sighted or heard about the Cayman Islands some time before 1503, a realization which requires further research as it complicates our understanding of the sequence of the events of that momentous time, which has perhaps been overly preoccupied with Columbus’ narrative.

As an archipelagic region which was at the center of these discovery and colonization campaigns, and which continues to have a geopolitical significance disproportionate to its size, while having produced a large diaspora of its own, maps and cartography have significant cultural, historical, and political importance to the Caribbean. The Cayman Islands have a unique maritime history within that context as a group of small islands in the expanse of the western Caribbean Sea. Turtle fishing, mainly in the waters around the island and the cays off the coast of Honduras, was once a major economic activity and Caymanians became known for their navigational and seafaring skills. In the modern era, shipping became another area of enterprise, now on a larger and more formalized scale, and many Caymanians joined the merchant marine. Nautical charts and more informal forms of navigation have played an important part in that history.

Today, the Cayman Islands are a major tourist destination and offshore banking center, which adds other dimensions to its position and identity on the global map. As perhaps the most rapidly developing island in the region, the physical and social landscape of Grand Cayman has changed dramatically in recent decades and over-development is now a major issue, especially in the western part of the island, while the eastern part is, at least for now, relatively untouched, with a large expanse of mangrove wetlands. Cadastral and subdivision maps have become a major part of contemporary life, with wetlands being drained and claimed for development, which changes the internal contours of the island. And as a low-lying and ecologically valuable but vulnerable island group, the prospect of being “wiped off the map” by sea level rise or a catastrophic event is not an imaginary one. Not surprisingly, maps, cartography and navigation have been a major inspiration to Caymanian artists, and 81° West: Cartographic Explorations in Contemporary Caymanian Art explores the various ways in which they have engaged with this theme. Next week, we will take a closer look at the exhibition itself.

Part 2

Previously, I introduced and provided context for the 81° West: Cartographic Explorations in Contemporary Caymanian Art at the National Gallery of the Cayman Islands (in which, for the sake of disclosure, I played a professional role as a curatorial consultant). This week, I will take a closer look at the exhibition itself.

Maps and cartographic processes, and their various uses and metaphorical implications, have been rich thematic and formal territory for Caymanian artists, in ways that are, because of the specifics of the islands’ maritime history, different from how artists elsewhere in the Caribbean have engaged with those issues. 81° West, which takes its title from the approximate longitude of Grand Cayman, takes a wide-ranging look at how Caymanian artists have engaged with these issues. The exhibition is divided into four thematic (and roughly chronological) groups, which is also reflected in its installation in the NGCI’s compact but well-appointed temporary exhibition galleries.

The first section, which starts with the maps and antique objects, is titled Points of Origin. The exhibition starts with an assortment of historical maps of the Caribbean, originals as well as a few facsimiles of rare maps that add to the conversation. Also on display in this section are a set of antique survey instruments and navigational tools that bring to life how these maps were created and used, and a few modern works that invoke the Cayman Islands colonial and seafaring history, such as Mangrove III (2005) by Chris Mann, which references Columbus’ first recorded sighting of Little Cayman and Cayman Brac in 1503.

The antique maps are hung in “salon style” fashion, arranged in the shape of Grand Cayman and it is remarkable how little it takes to successfully evoke this, as there is a significant level of public familiarity with the island’s striking, roughly U-shaped contours. This takes us to another dimension of maps and mapping, as what has been described as the “national logo-map,” as an emblematic image associated with the desire to celebrate and assert national identities, and a national sense of common cause. The Caribbean produces its share of “logo-map” pendants, and institutional and corporate logos in the shape of the respective islands. This “branding” of the national map is, for different purposes, also evident in the pictorial maps of the islands, with illustrations of their various landmarks and attractions, which are a staple in the region’s tourism industry.

Circumnavigations, the second part of the exhibition, takes a broader view of historical and symbolic associations of maps, travel, navigation, and, historically, the transition from small-scale turtle-fishing and informal wayfinding to global shipping and merchant marine travel, and its reliance on more formal navigation processes. Bendel Hydes (b1952), who is regarded as the first major modern artist in the context of the Cayman Islands, is a commanding presence in 81° West and fundamental to its premises. Most of his abstracted paintings and works on paper refer to maps, navigation, and travel, alluding to the Cayman Island’s unique maritime heritage, and his own family’s involvement in that history. The title of his Cayos Miskitos (1994) for instance, refers to the reefs and cays off the Nicaraguan coast that were frequented by Caymanian turtle fishermen. Combining place names, linear references to maps, archival photography and gestural abstraction, the painting powerfully evokes that maritime past without resorting to anecdote or sentimentality.

This second section of the exhibition also begins to explore the inherent parallels between cartographic and artistic processes, and its symbolic and psychological implications, which is one of the subthemes of the exhibition. As the section text panel explains: “Each of these artists can be seen to present their work as a surface encoded with meaning, suggesting—much like a ship’s captain who pores over the details of a nautical chart—that the role of the viewer is to decipher the signs, symbols, and linguistic clues that are inscribed within it.” This is explored further in the third section, To the Ends of the Earth, which features less literal and more abstracted engagements with the cartographic theme.

Davin Ebanks (b1975), a sculptor who works with found objects and glass, is represented in the exhibition with several stunning glass sculptures. Evoking the necessarily fluid and uncertain nature of location at sea in a medium that is both solid and fragile in its own right, works such Blue Meridian-81.2 W, Old Isaac’s (2009), an imaginary glass “slice” of the water at the location in question, symbolically assert and at the same time also question fixed notions of place and being. This work, by the way, also inspired the title of the exhibition.

The fourth and final section, New Horizons, focuses on responses to the present cultural moment in the Cayman Islands, at a time of rampant overdevelopment, significant demographic growth, and related social and cultural changes that challenge and complicate traditional conceptions of Caymanian identity. Back to Home (2016), by Nasaria Suckoo Chollette (b1968), playfully maps visual references to traditional aspects of Caymanian culture, in relation to the agents of change, such as tourism and Grand Cayman’s modern road network with its ubiquitous roundabouts, while Al Ebanks (b1963) captures the geographic and cultural disorientation arising from the rapid changes in the urban environment in his large-scale painting Walking on Shedden Road (2022).

The artists in this final segment also represent the most recent developments in contemporary Caymanian art, with new media and technologies and more conceptual and critical approaches that also challenge conventional notions of artistic authorship. Kaitlin Elphinstone (b1985) uses AI to manipulate and distort archival images related to Cayman’s maritime heritage, in ways that subvert our perceptions of the photographic image, and by implication also of maps, as incontrovertible “fact”, but also invite us to reflect in new ways on how heritage and past experiences inform contemporary identities. Elphinstone’s work also illustrates that AI, when thoughtfully used, can be a valid and productive artistic tool, rather than an existential threat to art and creativity, which is how it is seen by many.

Written in the Foundations (2023), finally, which is the second incarnation of a collaborative project by Kerri-Anne Chisholm (b1991) and Latoya Francis, offers an alternative cartographic approach, mapping social relationships and histories. In its original form, it was a site-specific project in North Side, Grand Cayman, that photographed and recorded conversations with local residents at different locations in the district and displayed the results on a disused building in this more traditional community. In the present exhibition, the project is represented by a series of polaroid photos, some of which had been on view in the community and are weathered, thus carrying their own place memories, along with polaroids that were not included in the original project and in pristine condition. The polaroids are arranged into a configuration that relates to the location of the documented sites and conversations in the community, in a way that echoes the arrangement of the antique maps at the start of the exhibition but serves as a subtle but poignant counterpoint to the generalizing dynamics of power, ownership and control expressed in the latter.

81° West will be on view at the National Gallery of the Cayman Islands until February 2, 2024.

Leave a comment